| Siberia and Beyond |

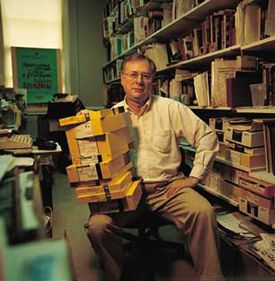

| William Craft Brumfield |

| brumfiel@tulane.edu |

| Photography By William Craft Brumfield |

To live in Russia is to come to a new understanding of space and time. The country devours

time because of its space--and the roads that cover that space. With characteristic

self-deprecation, Russians will quote their 19th-century proverb: "The only thing

Russia has in abundance is idiots and bad roads."

To live in Russia is to come to a new understanding of space and time. The country devours

time because of its space--and the roads that cover that space. With characteristic

self-deprecation, Russians will quote their 19th-century proverb: "The only thing

Russia has in abundance is idiots and bad roads." Then there is the climate. Everything takes more time when the temperature is minus 10 or 20, when every step on paths rutted with black ice is an invitation to disaster. Or in brief but fierce summers in a country that has no defense against 90-degree temperatures, except to retreat to shade and leave serious work for another time. Over the past three decades, I have done research and photography in some very distant parts of Russia, such as the far north, and I have gained great respect for drivers of all ages who have negotiated that terrain for me. Apart from native skills, they have an important ally from an unexpected source: the Russian automotive industry. The new Russians may have their Mercedes and Cherokees, but the true connoisseur of the Russian road prefers the UAZIK, Russia's equivalent of the classic Jeep. Four-wheel drive, two gear sticks, taut suspension, high clearance. Seat belts? Don't ask. The top speed is 100 kmh, but you rarely reach that if you drive it over the rutted tracks and potholed backroads for which it was designed.

The fact is, roads were an afterthought here. Settlers, hunters and traders moved over a network of rivers, lakes and portages that defined the area as geographically distinct. Indeed, the settlement of this part of northern Russia, its gradual development, and eventual assimilation by Muscovy were based on a paradoxical set of circumstances. The wealth of its forests, rivers, lakes and the White Sea promised considerable rewards to those capable of mastering the area; and yet the remoteness, relative paucity of arable land and length of the harsh winters discouraged growth. Those who succeeded in settling the area proved to be sturdy, self-reliant farmers and craftsmen, a mix of Slavs and Finnic tribes. Moscow colonized the area during the next two centuries, and by the reign of Ivan the Terrible in the 16th century, the Dvina River system had become Russia's primary path eastward to the Ural Mountains and westward to Europe. The importance of these routes faded after St. Petersburg's founding in 1703, but again became a critical artery during World War II and the Cold War submarine race.

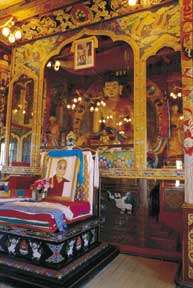

Such a large territory as the Russian North could easily have occupied the rest of my career. As a matter of fact, I continue my field work there on a regular basis with support from sources such as the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research, the American Council for International Education, the National Endowment for the Humanities and, of course, Tulane University. During the course of this work, I have witnessed the beginnings of environmental and social change brought about by major oil exploration in the north. But an altogether new dimension in my exploration of Russia came in 1999 when the Library of Congress and its director, James Billington, invited me to participate in a joint Russian-American cultural and educational program known as "Meeting of Frontiers." The program is based on the premise that for all of the obvious differences in Russian and American history and culture, there are significant parallels in the Russian move east and the American move west in pursuit of a national, transcontinental destiny. The fact that these two national movements end at the Pacific Ocean is the "meeting of frontiers." The goal of the program is to develop a bilingual Web site with a massive array of materials on the American West and the Russian East, including rare visual materials and documents from libraries in both countries. This site is available to anyone with Internet access, but the primary audience is teachers and students. My role was to photograph and document historic Russian architecture as a reflection of the Russian move east, from the Far North to the Far East, from the 15th century to the 20th. My previous years of work as a photographer and cultural historian had given me a thorough grounding in the European traditions of Russian architecture, but now I was to see that culture in a different, Eurasian setting. On Aug. 17, 1999, I hoisted cameras, film and copies of my published work on board the train at Moscow's Yaroslavl Station and set off for the east. Ultimate destination: Siberia. No geographical entity has more stereotypes--most negative--than "Siberia." Common usage in many languages has detached the term from its specific meaning to signify a brutish place of punishment. Yet with all the fervor of the lately converted, I now see that an understanding of Russia--in whatever discipline--is immeasurably enhanced by knowledge and experience of the north Eurasian land mass. [I should point out that my own work throughout this area benefited greatly from assistance provided by the historic preservation section at the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation.] My route followed the old path from Moscow to Vladimir and Nizhnii Novgorod, and from there to Viatka (now known as Kirov). There is a sense of boundary as the train crosses eastward over the majestic sweep of the Volga River and leaves behind the high, western river bluffs at Nizhnii Novgorod. Here is the broad conduit along which merchants from the Orient and nomadic invaders from Asia's highlands moved toward the ancient territories of the Slavs. And in the opposite direction, Russia's merchants, troops and settlers moved inexorably toward the east. Asia is still far, but Eurasia feels near at hand. Yet this is all still Europe. Kirov itself, located on picturesque hilly bluffs overlooking the Viatka River is not even the beginning of the end of the European continent. This ancient town, first mentioned in Russian chronicles in 1374 under the name Khlynov, arose in an area along the Viatka River that had been inhabited by Finno-Ugric tribes long before the first Slavs. Like so many other provincial Russian capitals, Kirov is struggling to modernize its economy while retaining a sense of cultural heritage. On the one hand, people rising to new positions of responsibility in the professional and administrative worlds show the signs of at least modest prosperity. On the other hand, the legacy of the 1998 financial crisis is still bitterly felt. These are not "new Russians," with money to burn, but white-collar professionals who looked forward to an increase in the standard of living. For them the devaluation of the ruble, although necessary to develop the Russian market, was devastating. This is particularly a problem for the many single-parent families created by Russia's high divorce rate. The daily frustrations are immense, yet these people understand that the only solution is to work toward the continued improvement of the system within which they live. At the same time, many are increasingly supportive of political factions that emphasize the return to a strong state system. As one of them told me, "Russians have always been a state people (gosudartsvenny narod)." Would this attitude change as I moved toward Siberia? The morning express train from Moscow leaves Kirov for Perm at 8, and for most of its distance the rail line to Perm follows the Cheptsa River. The beautiful rolling hills alternate with fields and forests. August weather varies greatly in this part of the world, and throughout the eight-hour trip, massive rain clouds alternated with sunlight that was all the more brilliant on rain-drenched leaves. Picturesque villages, many with stout log houses, alternated with the all-too-familiar scenes of industrial desolation: rusting, abandoned factories, reinforced concrete shells, tottering sheds. This detritus can be found in any industrialized country. But there is an unusually large amount of it in Russia, the legacy of a centrally directed state economy that wasted resources on a colossal scale and began hundreds of industrial building projects that were left unfinished when the money ran out and the state collapsed. Such thoughts were banished, however, as the train crossed the mighty Kama River and pulled into the Perm station on a rich, late-summer's afternoon. Perm is an attractive city with a cosmopolitan look to its main boulevards and a number of distinctive, pre-revolutionary neighborhoods. But for historic architecture, the smaller towns to the north such as Solikamsk, Cherdyn and Nyrob present a far richer array of monuments. Returning to Perm and taking the night train to Ekaterinburg, I finally crossed over the spine of the Urals, left Europe and entered Asia. Not that Ekaterinburg seemed any less European than Perm. Indeed, for those interested in the history of Soviet Constructivism, the architecture of Sverdlovsk (as the city was called in the Soviet period) is the best-preserved anywhere in Russia. Not even Moscow can boast of such a dense concentration. But for all the progress of the Soviet and post-Soviet period, Ekaterinburg is still best known as the site of the brutal murder of Nicholas II and his family in July 1918. Here, too, local architects and preservationists arranged travel for another historic town to the north--Verkhoturye, founded as a major transit point to Siberia for early Russian colonists, who could continue down the Tura River and eventually reach Tobolsk. Throughout my journey eastward, I regularly made trips north to regain the original Siberian trail, considerably to the north of the current main line, the "Moscow Road," established in the late 18th century. The symbol of Verkhoturye's pivotal role in extending Russian authority is its kremlin and church on Trinity Rock, high above the Tura River. What makes the Trinity Church so unique is not only its spectacular location, but also the rich combination of elements from the Italian Renaissance, medieval Muscovy, Ukrainian baroque, and a flair for ornament evident in the fagade's green ceramic work. Although the interior was ransacked and has only recently been cleaned and subject to basic repairs, the exterior is in superb condition, thanks to restoration work supervised by Elena Dvoinikova. My introduction to Siberia proper occurred, finally, at Tiumen, also on the Tura River. Tiumen is now flush with oil money, but it has managed to preserve much of the distinctive wooden architecture of its historic center, and a number of churches are being rebuilt. Particularly impressive are the early 18th-century "Siberian baroque" churches, with Ukrainian influence. From Tiumen I again made my way north, this time to Tobolsk, the 17th-century "capital" of Siberia. From its perch on high bluffs overlooking the mighty Irtysh River, the Tobolsk Kremlin (fortress) with its ensemble of churches and towers is one of the most impressive sights in Siberia. Most of the city's ornate 18th-century churches are still abandoned, yet a few have been restored to parish use, as has the Polish Roman Catholic church. After a week's trip back to the United States to check the camera equipment and develop the first 75 rolls of film, I resumed my Siberian journey in Omsk, also on the Irtysh River. The center of Omsk (current population around 1.2 million) has been relatively well preserved and not only conveys the prosperity in western Siberia at the turn of the century, but also suggests how much was lost by war and revolution. The theaters, hotels, banks and shopping galleries are remarkable even in a slightly dilapidated state. In addition to renovated Orthodox churches, Omsk also has two mosques, a beautifully restored wooden synagogue, and a large Evangelical Baptist church. Driving north from Omsk, along the Irtysh River, one sees grain fields that extend for hundreds of kilometers on all sides. My objective was Tara, another early (1594) settlement that defended the route east. Only one church, out of more than a dozen, survived the Soviet era. To look at pre-revolutionary photographs of such towns is to understand how much heritage has been lost. We went off-road to villages where small log houses reminded me of photographs of 19th-century settlers' houses in the American West. The poverty in these villages is deep, but the small towns are pleasant and give some idea of their resilience. After returning to Omsk, I journeyed on to Novosibirsk, a quintessential railroad town founded at the turn of the 20th century and now Siberia's largest metropolis. Here, elaborately decorated log houses from the beginning of the century co-exist with avant-garde Constructivist architecture and pompous Stalinist buildings. Much of the city's intellectual energy comes from the nearby scientific satellite town, Akademgorodok, where the staff at the Museum of the History of Siberian Culture showed me their famous collection of prehistoric Altai-region mummies--visited, I was proudly told, by Hillary Clinton. After Novosibirsk, I spent the next several days photographing other historic Siberian cities such as Barnaul, Tomsk, Krasnoyarsk and Yeniseisk. The train slowly wound through hill country whose autumn foliage was beautiful - in stark contrast to the disrepair and economic depression in the villages along the way. In Tomsk, I was met by friends from the excellent university, the oldest in Siberia. Tomsk is famous for its turn-of-the-century wooden houses with decorative carving that is the most elaborate in Russia. Dozens still stand, particularly in the Tartar quarter, whose White Mosque has been restored for worship. As elsewhere in my travels through Siberia, I saw a peaceful, multi-ethnic environment that seems distinctive to a region where just about everyone is from somewhere else. As is well known, many in this vast territory arrived through successive waves of exile. Yet there were many others who came as settlers, drawn by the lack of serfdom and the relative tolerance. Although it may seem strange to those used to old stereotypes, Siberia is now valued precisely for its greater freedom by many who live there. This is not to deny the lingering legacy of Stalinist and Soviet secrecy in places such as Tomsk, ringed with closed research institutes that can no longer pay their bills but continue to pollute the environment with various contaminants, some of them apparently radioactive. From Tomsk I took a slow train to Krasnoyarsk, a city of dramatic landscapes bisected by another great river, the Yenisey. Without divulging details, I can say that I traveled north from Krasnoyarsk 340 kilometers to the historic town of Yeniseisk. Here, the waters of the river are pure and the fish (tugun, sik, sterlet) is freshly caught--so fresh that it is often carefully sliced and served raw. I could not resist what my hosts had so beautifully prepared, one platter after another. The ultimate verdict--perfection, with a delicate texture that defies description! From Krasnoyarsk, I plunged ahead to the eastern Siberian city of Irkutsk, whose center is also well preserved from the days of pre-revolutionary prosperity. I am grateful to Nadezhda Krasnaya, director of the preservation office, for every courtesy extended during my stay. It was also my pleasure to consult with Boleslav Shostakovich, a professor of history at Irkutsk University and a specialist in the history of the Polish exile community in Siberia. (And, yes, Shostakovich is directly related to the same family as the great composer.) For all the destruction of the Soviet era, Irkutsk still has the most interesting church architecture of Asian Russia, including Orthodox churches with decorative elements that show the influence of Buddhist temples. Despite a cold snap, the Irkutsk weather in early October 1999 was idyllic, a perfect example of "golden autumn" and an ideal time to see nearby one of the world's great natural wonders, Lake Baikal. Irkutsk marked the end of my first Siberian campaign and the beginning of the second. After much winter, spring, and early summer fieldwork in the north of European Russia, I returned to Irkutsk at the beginning of September 2000 for the concluding phase of my Library of Congress work, a month that would take me to Vladivostok on the Pacific Ocean. During this period, I witnessed the consecration of the new Catholic Cathedral of the Immaculate Heart of the Mother of God in Irkutsk and saw the revival of Buddhism in Buriat areas beyond Lake Baikal. The end point, Vladivostok, had long been closed to Western visitors, but now it basked in fall sunlight (especially welcome after a series of typhoons spawned in the Sea of Japan) that reflected the hospitality I experienced there. Throughout these trips, I was impressed by a spirit of local initiative, especially in the study of regional history and culture. To be sure, there are many social and economic problems, whether in Arkhangelsk in the far north, or in Valdivostok in the far east. As for Siberia, its vast natural potential and beauty, exemplified by Lake Baikal, has been threatened by ecological blunders. To the extent that these and other problems are dealt with honestly, there is hope for their improvement through local, national and international resources. For all of these reasons, we must know more about this area. Siberia is approachable; it is not another planet. Indeed, its future will determine much that happens on our planet. William Craft Brumfield (A&S '66) is professor of Russian studies at Tulane. He currently is continuing his work in the Russian North as part of his 2000 Guggenheim award.

|

| Tulanian |

| Spring 2001 |

No place in Russia has more of such roads than

Arkhangelsk Province, which extends from the White and Barents seas in the north to the

Vologda Province in the south. A combination of poverty, government default and huge

distances have created some of the worst roads in European Russia.

No place in Russia has more of such roads than

Arkhangelsk Province, which extends from the White and Barents seas in the north to the

Vologda Province in the south. A combination of poverty, government default and huge

distances have created some of the worst roads in European Russia.  As a result,

Western visitors were banned from the area until the late 1980s and have only been able to

move with relative freedom since 1991. Although my introduction to the Russian North began

in 1988 with a trip to the fabled isle of Kizhi, my real study of that forbidding

territory began only in 1995, when I first arrived in Vologda, capital of the province of

the same name. Since then my cameras and I have made several forays to the Arkhangelsk and

Vologda regions in order to document the stunning, and perilously endangered,

architectural treasures of the Russian North.

As a result,

Western visitors were banned from the area until the late 1980s and have only been able to

move with relative freedom since 1991. Although my introduction to the Russian North began

in 1988 with a trip to the fabled isle of Kizhi, my real study of that forbidding

territory began only in 1995, when I first arrived in Vologda, capital of the province of

the same name. Since then my cameras and I have made several forays to the Arkhangelsk and

Vologda regions in order to document the stunning, and perilously endangered,

architectural treasures of the Russian North.